What Happens When I Burn Money?

20k words of analysis on what happens to the money (not the person who burns it)

If you think you have the definitive answer, or my characterizations of the arguments aren’t right, then please say.

Introduction

The deficits incurred in our attempts to tackle the economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic are pushing theories about money to the forefront of public discussion once again. Economic crises always cause us to question money.

What is it? How is it created? How does it work? What should we do with it?

Sometimes we respond by reinventing money. Like we did in 1694 when the Bank of England was formed to make a loan to the king in return for a monopoly on the issuance of banknotes. Other times we reimagine money. David Graeber’s seminal work Debt was written in response to the 2008 crisis and served to shift both the public and academic consensus on the nature of money.

A government’s response to crises is predictable. Christine Desan lays it out with perfect understatement in Making Money (p.296):

“A government that urgently needs money… has two alternatives. It can tax or it can borrow. The alternatives might even overstate the options.”

Borrowed money transforms crises into resolution but at a cost. The trauma is absorbed by the social body and sinks down to form a knot in our collective gut. The material discomfort associates itself to a thought that is itself already bound irrevocably to money. ‘How will we pay for this?’ we ask ourselves.

Money holds the pain of trauma. The social body ameliorates it not by discharging the debt itself but through distributing the pain in inverse proportion to each individual’s share of the sovereign currency. The less you have, the more hurts.

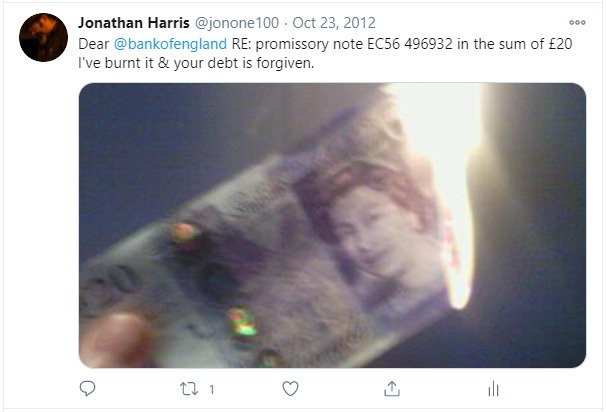

I used to say that when I burned £20 economic theory predicted that I was giving it to everyone else. But increasingly people are questioning that claim. They say I’m simply gifting my £20 back to the Bank of England and there’s no redistribution of the value represented by the note.

I don’t necessarily have a firm intellectual commitment to any particular economic narrative. I remain to be convinced that any single map can precisely chart the territory of money. And in truth, when £20 is burned what happens to the piece of paper is less important to me than what happens to the person who burns it. But equally, as a High Priest of the Church of Burn I have a duty not to mislead people and I must reflect substantive claims about ‘what happens when I burn money’ in my conversations with would-be burners.

As happenstance would have it, when I started writing this essay Verso Books were promoting economist Grace Blakley’s The Corona Crash — How the Pandemic Will Change Capitalism. As the title suggests, the book theorizes about the changes coronavirus might bring in its wake. Blakely believes it threatens to usher in a new era of monopoly capitalism and so makes her call for a radical response. To symbolise all this, Verso chose to use the image of a burning $100 bill.

Joachim Kalka says;

“…the tendering of a few coins over a shop-counter opens an abyss that reaches to the heart of the universe…”

If that’s right, then surely something truly extraordinary happens when a banknote is burned?

I’d like you to tell me what you think happens; either in the comments, or in a separate response that I can link to.

I think burning a banknote challenges the detached and contradictory discourse that dominates our conception of money and instead instigates an intimate and playful conversation between an individual and their economic cosmology.

Burning money for the first time marks a material change in an individual’s relation to it. Literally so. This is NOT insignificant.

A Word of Warning:

Although I hope this essay will appeal to everyone, I do go down some pretty deep rabbit holes. The central question of ‘What Happens When I Burn Money? might be reasonably and meaningfully answered by a scenic journey through the act’s symbolic or cultural significance. But this is not the path I’ve chosen. Instead, I’ve dug down into the theories that most immediately dominate our understanding of money, today. At times it can be an arduous journey that may test the will of even the most dedicated money nerd, let alone any companions who may be less enthusiastic about (or, perhaps unhealthily obsessed with) it’s arcane details.

If you find yourself trudging wearily at any point, unable to see through the gloom of detail, please hold my hand tightly and remember these promises; (i) you are never too far away from illumination by the next stunning, never-before-seen, photograph from Church of Burn 2019 (all courtesy of Jonathan Greet), (ii) the essay’s length (it’s 20k words) is testimony not my verbosity but to the elucidatory power of its central question; and finally that (iii) there is a special reward for anyone who makes it all the way through — watch the video at the bottom to find out more (don’t cheat, remember it’s as much about the journey as the destination).

One Übermode of Thinking & Three Logics of Money Burning

There’s no-one on Earth who’s been in closer proximity to more people able to answer from their own direct experience ‘What Happens When I Burn Money’ than me. I hope that doesn’t come across as bluster. It’s just the statement of a pertinent fact. As a High Priest of the Church of Burn I am in a privileged position. I feel that what follows then, arises from this. I’m inside looking out. I’m attempting to understand what is common to, and what divides, the various attempts to explain, analyse and critique money burning as they are directed at me and those around me. My position then might be described as ‘defensive’. And although I would reject a pejorative use of the word, I think it does have some merit because what I’ve tried to muster in this essay is a response that is precisely targeted at the threats as I see them. In my sights are those who seek to dominate the territory of money burning by dismissing, redefining, or in whatever way, contradicting my visceral experience of it.

So, I’m proposing that a quality of Explicitism is common to the discourse currently dominating our understanding of the nature of money. The discourse itself can be divided into three abstract schools of thought (or, as I’ll call them ‘Logics’) which I term Economic, Accounting and Financial — each has its own view about what happens when I burn money. I don’t propose these schools in concrete terms — although I do believe between them they cover the dominant conceptions of money. I accept that in practice economic theories can take a Hybrid Form — they can draw from any or all of the three schools — although I will argue that doing so risks logical coherence. Furthermore, I maintain that the dominant mainstream discourse on money does not have a properly conceptualised or coherent theory of Waste.

Explicitism:

I propose that Explicitism describes all modes of thinking that share a desire to ‘reveal what is hidden’. In practice Explicitism opposes the magical and mystical — that is, it opposes any mode of thinking (or being) whose unity is constituted by and dependent upon an ‘unknowableness’. In its essence however, Expliciticism exists as ‘exterior to’ rather than ‘in opposition of’ the magical et al. For Explicitism, mysteries exist as ‘unsolved puzzles’ and as such they provide an end point for its general movement. Explicitisism stands in close relation to Scientific Naturalism, Materialism and Positivism, but I maintain it is possible for a person to disavow say, Materialism, yet also practice a mode of thinking that is essentially Explicitist.

[ I’ve discovered that Explicitism and Implicitisim are terms used within Aesthetics. I do not claim my use of Explicitism here, mirrors its use there. ]

The Economic Logic of Money Burning:

With a fixed amount of cash in circulation at any one moment, my burning of £20 causes an increase in the value of money. After I’ve burned there is less money chasing the same amount of goods and services. The purchasing power of the remaining money rises and this is reflected by a relative fall in the price of goods and services.

The Accounting Logic of Money Burning:

When I burn £20 I am gifting the value of it to The Bank of England and, if they record my sacrifice, they can reduce their ‘notes in circulation’ liability by £20 thereby increasing their net worth by the same amount. In any event, the purchasing power of money in circulation is unchanged.

The Financial Logic of Money Burning:

As you’ll see later, I don’t really have an easily relatable explanation about what money burning means from within the operative Logics of Banking, Finance and Payments. But I’m pretty sure that they don’t think it’s a good thing to do.

Hybrid Forms:

As I’ve indicated by my use of the term ‘abstract’ to describe the three Logics above, I do not mean to suggest that general theories about economic life fall in line neatly and exclusively with only one school of thought. Theories of economy tend to give money a Hybrid form. Monetarism for example is based on the ‘Quantity Theory of Money’ which sounds very much like it needs money to be a material thing, a store of value that can be stacked up and counted, and is subject to (as I’ve defined the term) an Economic Logic. But I don’t think Monetarists would be happy with this, at all. They determine the ‘Quantity Theory of Money’ as an ‘accounting identity’. Not concerned with the things themselves but rather with their ‘flow’. They like to dematerialise money and talk about it being a ‘medium’; not only a ‘medium of exchange’, but also a ‘medium of account’ rather than the more common ‘unit of account’. One leading monetarist voice has recently called for us to drop the idea that money functions as a store of value altogether. [ — I’ll discuss the functions of money in detail later on. — ]

Waste:

At this early stage I want to note that the dominant mainstream discourse on money does not offer a properly conceptualised or coherent theory of ‘waste’. It upsets, as Noam Yuran says drawing on a Veblenian approach to economy, ‘any notion of utilitarian calculation’. Each of our three Logics (Economic, Accounting and Financial) regard waste as simply an undesirable outcome of their processes. They can only assimilate it by drawing it back into their respective logics and defining it within their own terms. Economics creates a commodity out of waste. Accounting creates a cost. And Financial Logic creates a sort of taboo. For all three, waste is opposed to productivity and efficiency and so it is a failure of process. And yet for human beings (at least for those able to resist the power of the three Logics to direct our every thought) our ability ‘to waste’ defines what is sublime to us — a day spent ‘just doing nothing’ can be the most precious of all. Examining money burning through the lens of these three Logics might then reveal as much about each of them, as it does about money burning.

[ — Chapter Five ‘Waste’ in Nigel Dodd’s The Social Life of Money is an excellent entry point into, and summary of, the ideas and theories that circumambulate money and waste. — ]

[ — To be as clear as possible and at the risk of repeating myself: I am not suggesting with the above that Economists believe this about money, Accountants that, and Finance the other. I’m simply trying to distinguish what is essential to the different modes of critique I’ve experienced as a money burner. — ]

Some General Points about Money Burning

Before we begin to dig deep and consider how each of the Logics may answer the central question, it might be helpful if I lay out a few broader points relevant to all three. When talking to someone about money burning I always first try to explain it in terms of it being ‘a form of ritual sacrifice’. A significant proportion of people instantly and instinctively understand and accept this. But many don’t. Sometimes people appear as nonplussed by money burning. Such a reaction is curious and — I suspect — inexplicable in direct terms. In other words, detaching oneself from any notion that one might deliberately destroy one’s own currency is really just a refusal to engage with its possibilities and meanings. Other times the mere contemplation of the act can provoke anger, moral outrage and derision. And this response is often directed toward me. What follows then are characterizations of the sorts of conversations I’ve had with people who’ve had this stronger emotional reaction.

1. Burning £20 is a waste of money. That £20 could have alleviated material suffering.

The Charity argument is reactionary and misconceived. At Church of Burn events, bar takings have always exceeded the amount burned in Ritual (in 2019 the sacrifice was £880) — and yet we have never once been criticized for the amount we spend on booze. We have however been heavily criticised (to the point of being threatened with disruption and protests) for burning money. Protagonists seem to feel there is a moral distinction to be made between spending money and destroying money. At one level this takes the form of a moral judgement about an individual and their choice to burn. But this is very shaky ground. The existence of Charities depends on ideas of economic sovereignty. Any moral opprobrium directed at a person should surely then apply to any form of non-essential or ‘wasteful’ spending? And then perhaps, it should be proportional to the absolute amount ‘spent’ rather than how it’s wasted.

At another level a rationale operates. Simply put it is that the ‘real value’ (that the £20 represents) is irrevocably destroyed by burning money. And so our capacity — as a society — to alleviate material suffering through production has been diminished by burning a piece of paper. An example of this argument in action can be seen in this interview with Gay Byrne and Bill Drummond.

Arguments at both levels are inconsistent with the principles and economic theories underlying them. Their end point is inevitably an extreme form of asceticism.

Related to all this is a false assumption very often made by observers that I don’t ‘want’ the money I burn. Unlike the Charity critique it is usually offered up as a light-hearted comment, rather than a moral condemnation. But even so it still reveals something profound. It has become so alien to the modern mind that one could desire something and yet choose to destroy it. Joke-making is the only way we can find to mitigate the contradictions and resolve the sense of awkwardness they provoke in us. And yet, simultaneously we have a profound knowledge of the sacred power of sacrifice and we instinctively understand that any sacrifice is not really a sacrifice unless something of value is given up.

2. My burning of £20 is so insignificant that it has no material effect and so it’s not really worth thinking about.

Money burning must hurt the individual, a little. There is a sweet spot for the pain which for most people, on an average wage, is usually between £20 and £50. Ultimately though, the right amount to burn can only be known by an honest reflection on one’s relation to money. In other words, what is burned must be significant to the individual in the moment of sacrifice.

In wider perspective of course, burning £20 to £50 is utterly insignificant; in the context of all sterling banknotes it is undeniably an infinitesimally small sum of money. But as well as pain, ‘pointlessness’ is crucial to the experience of sacrifice. If one believed that burning £20 would have measurable, material and direct economic consequences it would actually diminish the Ritual by turning it into another form of spending.

But equally, if burning £20 has no measurable material effect this begs a question; ‘Is There a Critical Point? If so, Where Is It?’ — in other words, if say £10 billion went up in smoke, would the effects be (a) my £20 burn magnified? or (b) or some completely different set of effects? These questions offer insights into the nature of money.

3. This is all academic — in the worst sense of the word — because burning money is just a really stupid thing to do.

There is a deep connection between money and thought. Not only in the sense that money sits in reflexive relation to the historical development of different modes of thinking — as Richard Seaford suggests for philosophy in Money and the Early Greek Mind, as Devin Singh suggests for theology in Divine Currency and Joel Kay suggests for science in Economy and Nature in C14th — but also in the sense that money and thought are intrinsically linked and remain formative of one another, today.

To dismiss the active negation of money or to be unwilling to consider the act’s psychological, cultural, social and economic implications is to kowtow to an inconsistent and contradictory taboo. The negation of money in speech (saying for example; ‘money isn’t important to me’ or ‘I’m not in it for the money’) is valorised to the extent that it can define an ideal of what is morally appropriate for a ‘good’ person.

But bizarrely, the actual negation of money — its wilful destruction by the act of burning currency — is seen by most (and I speak from personal experience) as heinous and immoral. In my view, the disavowal of this contradiction between speech and act — and a refusal to engage with moral and theoretical questions that arise from it — are symptomatic of a general failure to rise to the intellectual challenges that are presented by burning money.

[ — For a few related thoughts on this, please see my co-signed letter to the BoE in response to their Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) consultation. It makes the case that any CBDC should retain the capacity for destruction by its bearer. — ]

4. This is nonsense. No-one needs to burn their money to think about money.

The problem with this view is that it presupposes the value of intellectual knowledge over tacit knowledge and lived experience. Meaning comes from doing and value that exists in action that cannot be wholly captured in the data that action produces. I gave a talk at the Intersections of Finance and Society Conference in 2017 and I was asked by an academic ‘What does it feel like to burn money?’ It’s an astute question because the feelings invoked are important. But there is only one wholly truthful answer — ‘You have to do it, to find out’. Also, the experience of money burning is variable. It’ll depend, in part, on how you conceive of what you are doing. And in turn the feeling you get, may then alter your conception of the act. What has been true for me, fairly consistently and profoundly so on some occasions, is that money burning is a moral action.

More on the Economic Logic of Money Burning

The above video from Marc Poitras makes the case in plain language: ‘With one less dollar out there, all the other dollars are worth just a little bit more’.

A similar story is told by Steven Landsburg in his popular economics book The Armchair Economist.

Hollywood screenwriters and denizens of the college lecture circuit periodically rediscover the dramatic potential of a burning dollar bill. Typically the torching is accompanied by impassioned commentary — issuing from a sympathetic character on the movie screen or an aging cultural icon in the college gym — about how a dollar bill is nothing more than a piece of paper. You can’t eat it, you can’t drink it, and you can’t make love to it. And the world is no worse off for its disappearance. Sophisticated audiences tend to be uncomfortable with this kind of reasoning; they sense that it is somehow dreadfully wrong but are unable to pinpoint the fatal flaw. In reality, it is their own discomfort that is gravely in error. The speaker is right. When you spend an evening burning money, the world as a whole remains just as wealthy as it ever was.

Let’s think a little more deeply about what Poitras and Landsburg are saying; specifically about how the redistribution of value happens.

My friend Brett Scott from Altered States of Monetary Consciousness argues that burning a particular currency in cash, transfers — in the first instance — value to all the other holders of that particular currency in cash.

I’m not sure that the economic logic employed by Poitras and Landsburg suggests this. I think they imagine that when a particular currency, say $20, is burned the value is distributed across all units of that particular currency — whether they be in cash or bank balances (Poitras). And then any further adjustments that occur in other currencies — due to an increase in the value of the remaining dollars relative to goods and services — can happen through normal exchange mechanisms. Hence, Landsberg’s claim that ‘the world as a whole remains just as wealthy’.

Although no time scale is imagined within which the value from the burned note spreads around the world, a sequence of events does suggest itself. And I think that this is what Brett is tapping into. I have sympathy with his argument. It seems reasonable to suppose the thresholds between different forms of currency — say between cash and bank balances — mark a boundary that must be negotiated by the value emanating from the burned note. I’ll come back to this idea of boundaries later when I talk about money and law in the section after next.

More on the Accounting Logic of Money Burning

This view sees my burning of £20 as a de facto internal adjustment to the balance sheet of the issuing central bank — in my case The Bank of England. This adjustment has no real effect on the value of money in circulation.

Here’s a recent tweet thread from Wolfgang Theil rejecting the Economic Explanation:

Here is a tweet from James Zdralek making a similar point:

I should discuss the point that Wolfgang raises. Do the Bank of England know about the destruction of their notes?

Personally, I’ve only told them about one burn directly (see below). I got no response. But I also run a public ‘Record of Burn’ which details (as of 12 November 2020 ) the destruction of currency worth £2,684,999. The Record of Burn actually records all forms of currency destruction and, in some cases, provides evidential support of the destructive act.

According to Wolfgang, if a Central Bank decides to record my burning of £20 then there is a positive accounting consequence for them. Its liabilities are reduced and so its balance sheet becomes healthier. Conversely, if the Central Bank ignores my destruction of its currency, its balance sheet is unchanged. The debt remains on their books as a liability even though it has — in effect — been irrevocably forgiven.

However, for as long as they fail to record my act of debt forgiveness, EC56 496932 (£20) actually continues to provide an income for the Bank of England (details of how this magic trick is performed can be found on the BoE’s website — see point 1). Hence, James Zdralek’s claim that my ‘burn becomes perpetual income for central bankers’.

More on the Financial Logic of Money Burning

As I’ve already stated and as I’ll discuss again later on, I’m not convinced that the Financial Logic associated with the praxis of money is able to offer a coherent and consistent view on what it means to burn money. I suggest this is because they value pragmatism over rigor in their conception of money. This is understandable and appropriate. They need an idea of money that works ‘in practice’ and so their conception of it is malleable. It becomes a ‘working fiction’ that has an appearance of consistency but actually can be moulded to the narrative that’s most efficacious to praxis, at any given moment.

Financial Logic is of course the most powerful of the three in terms of its practical ability to affect the constitution of social reality. They do have all the money, after all. Financial Logics subsume both the Economic view that money represents some claim on real resources and the Accounting view that money is really just a number, not a thing. They contain these multitudes by talking in terms of money being a ‘generalized means of exchange’ and such like. I’ll talk more about that later on, too.

But for now, I want to just highlight one of the stories Financial Logic tells us. It’s about money being at its heart a payments system that depends on agreements, regulations and laws.

I stress this story because it seems to me to offer most hope in terms of understanding what insight Financial Logics might offer in respect of what it means to burn money. But also it has to do with the notion of ‘borders’ that I mentioned in the Economic explanation and so it might help elucidate that idea, too.

Many — adherents of Modern Monetary Theory, most especially — believe that Law is constitutive of money. That is to say that the Law doesn’t merely define how we deal with money but is profoundly implicated and present within the nature of money itself. I don’t share this belief. I hold to the following:

…that the question of what can be treated as money under the law has: “nothing to do with a quite different problem; what is money in an abstract sense, what is its essence, its intrinsic attribute, its inherent quality?”

Essentially I believe that Law reacts to something we call money. The form money takes (that is, how it appears as currency) might be, and usually is, affected by Law. But for me Law is not money’s essence.

I’m not a legal scholar and I know many adherents to Modern Monetary Theory have a deep understanding of Law as it relates to money. So I want to be as precise and upfront as I can here. The quote above comes from a key legal text on money;

Fredrich Mann’s The Legal Aspects of Money (1992) as it appeared in Nigel Dodd’s The Sociology of Money (1994) [ — p.28 in both books — ].

Mann’s book was first published in 1938, is regularly updated and a new version (8th edition) comes out in July 2021. It costs £295 so it’s not going to be an addition to my poor man’s library of money books. However, I did manage to ‘borrow’ the seventh edition published in 2012 — the title has been changed reflecting Mann’s death in 1991. The author is now Charles Proctor and the book is titled ‘Mann on the Legal Aspects of Money’. Mann’s 1938 musings on the relation of Law to the nature of money, that I’ve quoted above, do not appear in the seventh edition. Mann’s humility, has been excised in 2012 for Procotor’s more robust “The troublesome question, ‘what is money?’ has so frequently engaged the minds of economists that a lawyer might hesitate to join in the attempt to solve it. Yet the true answer must, if possible, be determined. For ‘money answers everything’.” (Section A 1.01)

But let’s put myself, Fredrich Mann and Nigel Dodd aside for the moment and contemplate how it could be that money is fully a creature of Law.

First thing to ask yourself is do you consider the balance in your bank account to be money? The answer for most of us is ‘yes’. It is these days the stuff we use most often to buy things, so it seems to work pretty well as money. But dig down into the rules by which International Banking operates [the Uniform Commercial Code] and you find that your bank balance isn’t actually regarded as money at all. Only currency is money (effectively that’s notes, coins, and central bank debt — which is what notes and coins represent). Your bank balance is a mere right to currency. At first sight this seems to negate the idea that money is a creature of law. However, as the legal scholar Joesph H Sommer explains, the distinction between the notes in your wallet and the balance in your bank prevents a very real problem; an infinite regress. If your bank balance — which is in fact your bank’s liability — is money, then ‘the monetary payment of a debt is satisfied by the monetary payment of a debt.”

You can actually have a wonderful day out at the Bank of England experiencing this distinction between commercial bank money and cash (i.e £ banknotes) in real time, as I did in April 2016. I wanted to get some brand new notes to create a money collage. £230’s worth to be precise. So I went to London to visit the Bank of England’s public counter. As I walked in, I was stopped and asked about the purpose of my visit. I said I wanted to get £230 in cash. The security officer demanded that I show him the money I wished to exchange for the £230. I was a little confused. I said, ‘Er, I was just gonna pay on my debit card.’ He refused me entry to the public counter telling me that in order to get £230 from the Bank of England I must present £230 in cash. He told me there was a cashpoint just down the road at NatWest. So I went there, took out £230 (changed my claim on currency into actual currency), went back to the Bank of England and I was then allowed entry. I gave over my £230 at the public counter and was given £230 in exchange (in nice crisp brand new notes). [ I did a similar thing in 2017 but had a different and less reassuring experience. ]

To return to Sommer’s point about infinite regress. He goes on to say:

“….infinite regress can be broken by what amounts to a leap of faith: an epistemological emphasis on the social construction of money. To phrase these words more succinctly, money is what payment systems do. The legitimacy of money, therefore, arises from our acceptance of the underlying payment system rules. These rules are nothing more than the homely law of bank liabilities and the law governing the transfer of these liabilities. As long as we collectively accept these rules, the infinite regress is not a real problem. If we do not collectively accept these rules, even currency is worthless.”

Joseph H. Sommer Where is a Bank Account? (1998)

Sommer’s rules can then, I suggest, be thought of as ‘boundaries’ between different forms of money (between banknotes and bank deposits). And moreover, the direct implication of Sommer’s claim — ‘If we do not collectively accept these rules, even currency is worthless’ — is that the rules or boundaries, and our collective acceptance of them, are what gives value to money.

You can see a correspondence here with Brett’s idea that there is a boundary between cash and bank balances and that a burned note transfers its value only to other holders of cash.

In physical form boundaries have an ancient relation to economy and not only in the obvious sense of sovereign territories. Statues of Hermes marked both the marketplace itself and its boundaries in ancient Greece. And today in our digital world, a failure to update boundaries in response to money’s changing technologies — such as on which side of the banknote/bank-deposit fence a stablecoin sits — is seen as critical in allaying or mitigating financial and economic instability.

To finish then by returning to the question of what happens when I burn money according to Financial Logic. I must admit I’m still confused as to what the logic predicts. A banknote (currency proper) appears to be something that while it’s treated as something special in the legal constitution of money, it actually isn’t special at all. Burning one then appears to be an action which is both meaningful and not meaningful. It has real financial (accounting and economic) effects but simultaneously has no real effect at all. It merely destroys an imaginary boundary which in the course of our ordinary lives (i.e. outside of legal theories of money) none of us really care about. It’s equivalent to me getting a UK atlas off my bookshelf and redrawing the borderline on a map of Wales to annex Bristol. My action is real, its effects are not.

A Discussion on the Functions of Money

We’re already quite far down the rabbit hole. But we’re going to go much, much deeper. I’d love it if you’ll come with me, but if you need to dig upwards to get some air and then meet me again later on here is a sentence to explain where I’m going: I want to show how despite the fact that a functional approach to money underscores all dominant discourse it’s not logically coherent to the practice of money and it causes harm to society.

I’m going to use the ‘three functions of money’ model in order to dig into the three explanations I’ve characterised above. Listed in no particular order, the three functions of money are; medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Vestry to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.